In this article, I will debunk the five arguments fascists currently use to target transgender people. All fascist movements are predicated upon the myth of categorical purity. Because the material reality of individual humans is not one defined by discrete category, fascism always seeks to conflate people with words and category. It is for this reason that fascism is incompatible with human flourishing.

1. Individuals are category

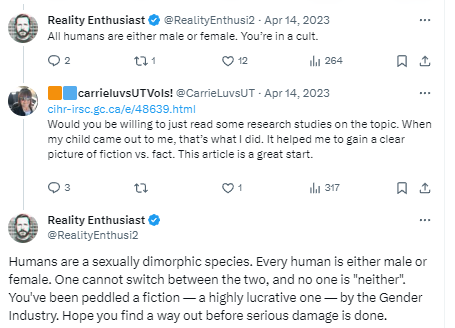

“People are either a man or a woman. Humans are a sexually dimorphic species!”

Let us apply the logic of such statements to a more apparent human attribute to bring the fallacy of such a dialectic into focus:

“Humans are a bipedal species. Therefore, a human born without legs needs shoes because they are human.”

This argument conflates category with individuals. Humans, as a categorical construct, are sexually dimorphic and bipedal. This does not mean that each and every human, by virtue of their humanity, must therefore be sexually dimorphic or bipedal.

2. Categories are natural

“You’re a biological male! Using male pronouns is merely a recognition of that reality. It’s not transphobic!”

This argument conflates the meaning of “biological” in the categorical sense with “biological” in the living matter sense. Such arguments come into focus when we remove the equivocation:

- “You’re a categorical male!”

- “You’re an ontological male!”

When one says, “biological male” or “biological female,” their linguistic construction is a tautological assertion that one is categorically category.

The fallacy is obscured because most people take the rhetoric to reference a state of living matter. But such rhetoric can begin to seem problematic when we say what people tend to take this rhetoric to mean:

- “You’re a living male!”

When we clearly debate whether trans people are alive in the sense that cis people are alive, such rhetoric can be correctly apprehended as being rooted in fascism. All humans, whether they be cis, intersex, or trans, are, in fact, biological in the sense that we are made of living matter. All cis, intersex, and trans women are biological women, and all cis, intersex, and trans men are biological men. The dialectic of “biological male” and “biological female” is particularly insidious because once an oppressed minority ceases to be “biological,” practically any form of oppression enjoys rhetorical plausibility.

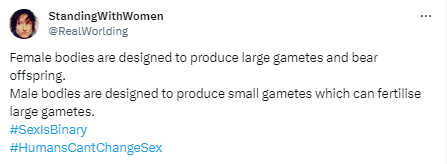

3. Categories are essential:

“You’re either male or female! Male = small gametes and female = large gametes.”

Here, the appeal is to essentialism; that which is the quintessence of sexed category, in this case, gametes, are asserted to be that which defines bodies. However, those making this argument would certainly balk at the following claim even though it is predicated upon their own logic:

“Baby boys are girls because they do not produce small gametes.”

The reality is that nobody uses the presence or absence of gametes to define sex as such would result in three categorical sexed positions: people with small gametes (the male sex), people with large gametes (the female sex), and people with no gametes (a third sex).

The reality is that all people do not produce gametes at various times of their life and some people never do. Regardless, their sexed identities remain. A baby boy is a baby boy even though he is a decade or more away from producing gametes.

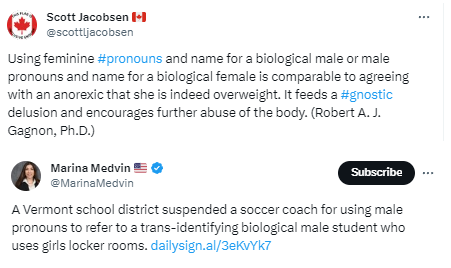

4. Categories are designed:

“You’re either male or female! Your body is either designed to produce small gametes or designed to produce large gametes.”

Here, the functionalist argument is two steps down the fallacious dialectic of categorical purity. For one to find this dialectic of design compelling, one must already accept objectification predicated upon essentialism:

- Objectification: people are category.

- Essentialism: category = an essential attribute.

- Functionalism: the essential attribute is the reason for people’s existence.

Functionalism is the ideology underlying the whole of patriarchy and is the very basis of TERF ideology. Interestingly, it underpins modern American evangelical ideology as well, which is why TERF groups often materially support far-right organizations and far-right organizations fund TERF groups. Moreover, for both TERFs and the far-right, the will of the designer must never be questioned. For TERFs, it’s Nature’s will that must be honored, and for the far-right, it is their God’s will.

Nature or a God deemed us to be category and category we must be. Those who dare to design their sexed attributes in accordance with their own will are mutilating or desecrating their bodies. Either way, such is a freedom that trans (and oftentimes intersex) people should never enjoy.

Never mind the whole of the multi-billion-dollar health, diet, wellness, and beauty industry is supported by cis people who are trying to construct and accentuate a sexed body binary we are told is natural. This is to say nothing of the common US practice of performing cisgender-confirming sex surgery upon most baby boys even as it kills 100+ each year.

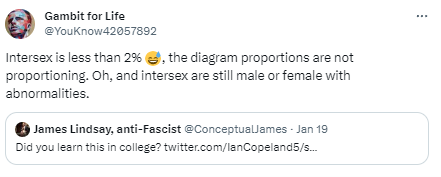

5. Categories must be pure:

“People are either male or female! Intersex people only make up something like just 2% of people. It’s anti-science to claim there’s more than two sexes!”

Let us apply the logic of such a statement to another scientific concept to bring its fallacious nature into focus:

“Matter is either hydrogen or helium! The other matter makes up something like just 2% of matter. It’s anti-science to claim there’s more than 2 material states!

While it is true that hydrogen and helium comprise 98% of the matter in the universe, we can immediately spot the problem with appealing to the nature of purity.

Those of any minority group will find these fallacious dialectics familiar. They are the arguments Frantz Fanon considered in terms of the material history of the Black experience.[1] Likewise, they are the same dialectics Simone de Beauvoir,[2] Monique Wittig,[3] and Andrea Dworkin[4] repudiated in their explications of the material history of the sexed experience.

Consumers of the philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre,[5] Friedrich Nietzsche,[6] Søren Kierkegaard,[7] Albert Camus,[8] Martin Heidegger,[9] Maurice Merleau-Ponty,[10] Edmund Husserl;[11] the works of classical “Western” thinkers such as Socrates[12] or “Eastern” Buddhist thought;[13] or, even some of the great novelists such as Fyodor Dostoevsky,[14] Franz Kafka,[15] Hermann Hesse,[16] Kurt Vonnegut,[17] or even John Green[18] will be familiar with encountering the logical fallacies underlying many of the above dialectics.

Given this, it is always interesting to me to see members of other oppressed groups using these dialectics against trans people. I’ve always noticed that TERFs talk about the bodies of trans women the way that misogynists talk about the bodies of cis women. This, then, seems to be why fascists have, since at least WW II, targeted trans people when recruiting voters to their effort to define structural power. Problematically, members of historically oppressed classes who join fascists in targeting trans people wrongly believe that in joining in fascist oppression, they’ve earned a seat at the fascist’s table, when, in fact, they’re on the menu.

[1] Frantz Fanon, a psychiatrist and political philosopher, argued against the notion of people being discrete, unchanging categories, particularly in the context of race, identity, and colonialism. His arguments are primarily found in his influential works, Black Skin, White Masks, and The Wretched of the Earth. Fanon critiqued the rigid categorizations of identity that were often used to justify colonialism and racial discrimination. He emphasized that the identities of individuals, especially those who are colonized, are not static or inherently bound to certain categories. Instead, these identities are dynamic and shaped by a range of sociopolitical factors, including colonial power dynamics. Fanon’s analysis extended to how colonized individuals internalize the perceptions and stereotypes imposed on them by colonizers, leading to a fractured sense of self. He argued that the process of decolonization involves a psychological liberation as well, where individuals redefine and reclaim their identities beyond the confines of colonial narratives.

[2] Simone de Beauvoir’s argument that “sex” cannot be reduced to any essential body attribute is a central theme in her seminal work, The Second Sex. Her famous statement, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” encapsulates this idea. Furthermore, Beauvoir explored the concept of ‘the Other’, analyzing how women have been historically marginalized and defined in relation to men, who were considered the norm or the default. This othering of women perpetuated the notion that women’s experiences and identities were secondary or derivative, rather than being independently valid. While the American feminist, Ruth Herschberger explored these issues in her book, Adam’s Rib, it was de Beauvoir’s work that profoundly influenced feminist thought by challenging biological determinism and highlighting the importance of social and cultural factors in shaping gender identities.

[3] Monique Wittig made significant contributions to feminist thought, particularly in her argument against objectifying women as a category. Central to Wittig’s philosophy was the idea that ‘woman’ as a category is a social construct, primarily used to enforce heteronormativity and patriarchy. Wittig posited that the concept of ‘woman’ existed to perpetuate social structures that maintain traditional gender roles and power dynamics, particularly in the context of heterosexual relationships. She argued that this categorization serves to uphold the notion of women as inherently different and subordinate to men, thereby legitimizing their oppression and marginalization so that the category of ‘woman’ functions a tool of patriarchal society to enforce heteronormativity and marginalize those who do not conform to it. Her work encourages a rethinking of gender and sexuality in ways that liberate individuals from predefined categories, allowing for more fluid and self-defined identities.

[4] In Woman Hating, Andrea Dworkin critiqued essentialism and its role in objectifying women. Dworkin argued that essentialism, which is the belief in fixed, inherent attributes defining men and women, contributed to the objectification and subjugation of women. She contended that by defining women through a narrow set of supposedly innate characteristics or qualities, typically in contrast to men, society effectively reduced women to a category. This categorical view, she believed, was not based on the complex reality of individual women’s lives but rather on a simplistic and often stereotypical understanding of “femininity.” Dworkin’s critique was focused on how these essentialist views were used to justify and perpetuate gender inequality. By framing “woman” as natural, essentialism reinforced the idea that women’s place in society was predestined and unchangeable. This, according to Dworkin, was a form of objectification, as it denied women their full humanity and individuality, reducing them to mere embodiments of abstract concepts of “womanhood.”

[5] Jean-Paul Sartre, argued against essentialism, particularly in the context of how it objectifies people. Sartre’s primary argument was that ‘existence precedes essence.’ In other words, individuals aren’t born with a set of fixed, inherent attributes (essence) that define their identity or purpose. Sartre was concerned with how essentialism reduces individuals to a category or a collection of stereotypes, stripping them of their individuality and freedom. Essentialism, by asserting that certain characteristics are inherently tied to a particular group (be it based on gender, race, or any other category), denies the complex and unique nature of human existence. Sartre argued that this kind of categorization overlooks the personal experiences and choices that truly define a person. For Sartre, when people are objectified as a category, they are viewed not as autonomous, free individuals capable of self-definition, but as mere embodiments of pre-defined characteristics. This perspective fails to recognize the fundamental freedom of individuals to define themselves and their world. It also leads to a deterministic view of human behavior, which is at odds with Sartre’s belief in human freedom and responsibility.

[6] Friedrich Nietzsche challenged the traditional philosophical and moral concepts that posited the existence of fixed, universal truths or essences. He was particularly critical of the ways in which these concepts were used to categorize and objectify people. Nietzsche’s perspective on essentialism and its role in objectifying people is seen in his critique of social systems, asserting that these systems imposed artificial structures on human experience, reducing individuals to mere examples of metaphysical categories, rather than acknowledging them as dynamic, self-determining beings. He saw essentialist categories as tools used by societal and religious institutions to control and diminish individuality, advocating instead for a recognition of the fluid and self-created nature of human identity.

[7] Søren Kierkegaard argued that human beings cannot be fully understood through broad, essentialist categories, as these fail to capture the depth and complexity of individual experience, noting that everyone’s existence is unique and cannot be reduced to generic categories or definitions. In his view, essentialism tends to objectify people by placing them into predefined categories, thus stripping them of their individuality and subjectivity. One of Kierkegaard’s key concerns was how such categorization overlooks the individual’s personal relationship with existence, including their emotions, choices, and dilemmas. He believed that true understanding of a person comes from acknowledging and engaging with their subjective experience, rather than applying universal labels. He saw essentialist categorization as a form of objectification that fails to respect the depth, ambiguity, and fluidity of human life.

[8] Camus’ philosophy centered around the concept of the absurd, which is the conflict between humans’ search for inherent meaning and value in life and the universe’s indifferent response to this search. From this perspective, he argued against the idea that life has an intrinsic essence or meaning, suggesting instead that meaning is something individuals must create for themselves in an inherently meaningless world. In this context, Camus’ argument against essentialism can be understood in terms of his rejection of the notion that people can be categorized based on inherent essences or predefined attributes. By emphasizing the individual’s personal journey in a world devoid of inherent meaning, Camus implicitly argued against reducing people to mere categories, believing that each person’s experiences, choices, and struggles are unique and cannot be fully understood or defined by broad, essentialist categories.

[9] Martin Heidegger critiqued essentialism, particularly in the context of understanding human existence, arguing against the reduction of human existence to static categories or essences. Heidegger’s key philosophical work, Being and Time, introduced the concept of “Dasein,” often translated as “being-there” or “existence.” In his exploration of Dasein, Heidegger emphasized the dynamic and ever-changing nature of human existence. He argued against the traditional metaphysical notion that a person’s essence—what one is—precedes their existence. Instead, he suggested that the essence of being is fundamentally tied to and revealed through its existence in the world. Heidegger’s focus was on the individual’s lived experience and the meaning they derive from their interactions with their surroundings. He explored how people’s understanding of themselves, and their world is constantly in flux, influenced by their experiences, choices, and the context of their existence.

[10] In his seminal work, Phenomenology of Perception, Merleau-Ponty argued that human perception and experience are grounded in the lived, embodied experience, challenging the traditional Cartesian dualism that separates mind and body. He posited that our bodies are not mere objects in the world but integral to how we experience and understand the world. This perspective inherently questioned essentialism, which tends to abstract human qualities from the lived, embodied reality and categorizes people based on presumed inherent attributes. Merleau-Ponty emphasized the fluid, dynamic nature of experience and existence, arguing that people’s identities and understandings are constantly shaped and reshaped through their interactions with their physical and social environments. He argued that such categorizations often fail to capture the richness and complexity of human existence, reducing individuals to mere stereotypes or abstractions that couldn’t be adequately captured by static, essentialist categories.

[11] While the founder of phenomenology, Edmund Husserl didn’t explicitly focus on essentialism in the context of objectification, his philosophical approach provided the foundation for understanding and critiquing essentialist claims. Husserl’s main philosophical endeavor was to explore the structures of consciousness in terms of experienced phenomena. He developed a method known as “phenomenological reduction” or “epoché,” which involved setting aside biases and preconceptions, including essentialist notions, to engage with the direct experience of phenomena. While Husserl himself did not directly engage with the notion of essentialism as a tool for objectifying people, his emphasis on subjective experience and the bracketing of preconceived notions can be seen as foundational for later critiques of essentialism. His work laid the groundwork for a more nuanced understanding of human experience, one that recognizes the limitations of categorizing people based on ‘natural’ or ‘god-given’ attributes.

[12] Socratic philosophy does offer insights that can be related to these themes of questioning the instinct to reduce people to category through essentialism. Known for his method of inquiry, often referred to as the Socratic Method, which involves asking probing questions to stimulate critical thinking and illuminate ideas, challenging axiomatic presuppositions, and encouraging a deeper exploration of concepts and beliefs. He often questioned commonly held notions, asking his interlocutors to define these terms and in doing so, he demonstrated how people’s understanding of such concepts was often superficial and based on unexamined beliefs. While Socrates sought universal definitions for these concepts, his approach was not essentialist in the modern sense, in that he wasn’t reducing individuals to fixed categories but was rather seeking to understand the underlying nature of humanity. In this way, he precipitated the very critiques of essentialist reductionism considered in this article.

[13] In Buddhism, the idea of a fixed, inherent essence in individuals or things is seen as an illusion. Instead, all phenomena, including human beings, are understood to be in a constant state of flux, changing and interdependent, positing that what we typically think of as the ‘self’ is actually a composite of constantly changing aggregates: form, sensation, perception, mental formations, and consciousness. By rejecting the notion of a permanent self, Buddhism inherently critiques the process of categorizing people based on any supposed inherent essence. The tendency to label and objectify people as part of fixed categories is seen as a source of misunderstanding and suffering. Such categorizations are considered a byproduct of human desires and aversions, which Buddhism teaches to transcend. Moreover, the Buddhist emphasis on “dependent origination” (Pratītyasamutpāda) further counters essentialist thinking. This concept describes how all phenomena arise in dependence upon a network of causes and conditions, meaning that nothing exists in isolation or with an independent, self-contained essence. I wrote about Buddhist trans acceptance vs. bigotry here.

[14] Fyodor Dostoevsky, in his profound and complex narratives, often explored themes of how human suffering, morality, and angst were associated with reducing individuals to simple categories, demonstrating the inadequacy and danger of attempting to understand people based on superficial or rigid categories. His characters often suffer as a result of being misunderstood, misjudged, or reduced to a single aspect of their identity by others, reflecting the limitations and harm of essentialist thinking. For instance, in The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky explores the depths of human psychology, illustrating how reducing individuals to fixed categories fails to capture the true essence of their experiences and leads to misunderstandings and conflict. In Dostoevsky’s universe, the suffering of his characters often arises from their struggle against the societal, religious, or ideological categories imposed on them.

[15] Franz Kafka’s stories consider themes of alienation, anxiety, and the oppressive nature of societal structures, indirectly critiquing reductive essentialism and the objectification of individuals. While, like many authors, Kafka does not explicitly frame his narratives around a philosophical discourse on essentialism, his work often depicts the struggle of individuals against an opaque and indifferent system that treats them as mere subjects to be processed and categorized, rather than as individuals with their own unique experiences and identities. His characters frequently experience a loss of identity and autonomy, symbolizing the dehumanizing effects of being pigeonholed into rigid societal roles and expectations. In stories like “The Metamorphosis,” Kafka vividly illustrates the psychological and existential impact of being seen only through the lens of one’s utility or social role. Through his exploration of themes such as alienation, bureaucratic oppression, and the absurdity of existence, Kafka’s stories critique reductive essentialism and the suffering it causes. His narratives underscore the dangers of a world where people are objectified and defined by narrow categories, losing their individuality and humanity in the process.

[16] Hermann Hesse’s literary works often explore the themes of self-discovery, individualism, and the critique of societal norms, including reductive essentialism. He argues that the imposition of rigid, reductive categories on individuals leads to suffering and a loss of true identity. Hesse’s characters frequently embark on journeys of self-exploration, seeking meaning and identity beyond the confines of societal roles and labels. This quest often involves a rejection of conventional categorizations and deep introspection to understand their unique, individual experience. Hesse’s narratives underscore the psychological and existential impact of being forced into reductive categories and highlight the importance of personal journey and self-realization, which are central to the trans experience.

[17] Kurt Vonnegut’s narrative style and thematic explorations often explore how reducing people to simplistic categories leads to dehumanization and suffering. His characters often find themselves trapped by the absurdities and cruelties of societal systems that prioritize conformity, efficiency, and utilitarianism over individual human experience and value. These systems, whether they are governmental, corporate, or military, tend to categorize people in ways that strip them of their complexity and individuality. Vonnegut’s depiction of systems that reduce individuals to categories or functions reflects the real-world experiences of marginalized and oppressed groups. These groups often face stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination based on reductive and essentialist views of their identities. He underscores the importance of seeing people as complex individuals with their own stories, experiences, and values, rather than as mere components of a larger system or as representatives of oversimplified categories.

[18] John Green often addresses themes of identity, suffering, and the human experience. His narratives typically explore the complexities of his character’s inner lives, challenging reductive essentialism and the categorization of individuals. His character’s experiences highlight the emotional and psychological impact of being objectified or labeled, emphasizing the importance of seeing people as complex individuals with their own unique stories. Oppression is predicated on the reduction of individuals to mere categories or stereotypes, overlooking their personal experiences and identities and Green’s stories resonate with the need to acknowledge and appreciate the complexity and diversity of human experience, particularly for those who are marginalized or oppressed.